A short look back at a travelogue from the year 1907 by Wilhelm Rickmer-Rickmers

When Ella Maillart visited Central Asia, all activities in the Central Asian Soviet Republics were dominated by the fulfilment of the first five-year plan. During this time, Maillart still writes of the region as Turkestan, which had been called Russian Turkestan before the Bolsheviks‘ conquest. The German explorer Rickmer-Rickmers had described the region as Duab with colonial gestures in 1907 during his lecture to the Royal Asian Society.

The word means ‚two rivers’, and was chosen by me on the analogy of Punjab, or ‘five streams’. Its outline is easily remembered, for the two mighty rivers, the Oxus, or Amu, and the Yaxartes, or Syr, form the greater part. To complete this boundary, we have only to draw a straight line connecting the estuaries in the sea of Aral, and another, along the watershed from the sources of the Oxus to where the Naryn, or Upper Syr Darya, comes out of the Ferghana Mountains.

Rickmer-Rickers, Impressions of the Duab (1907)

Rickmer-Rickmers called the region the ‚California of Russia‘ in 1907 because of the enormous agricultural potential of irrigated farming. He found it positive that the land was completely controlled by the strict Russian rule and was increasingly developed by railways, roads and canals. Industrialisation and modern urban development were, in Rickmer-Rickmer’s view, only a matter of time. He was accompanied by his wife, the Austrian mountain climber and photographer Cenzi von Ficker and his translator Makandarov. However, he also foresaw a future in which the rivers Amu Darya and Syr Darya would no longer reach the Aral Sea.

After the commercial boom will come industry and mining. But, above all this, there looms large the work of the country – the result of a century – irrigation. The waters of the Oxus and Yaxartes still flow into Lake Aral. The great task of the future will provide work until the last drops of these rivers have been diverted to agriculture. Realize this: not until Lake Aral is dry, we need to expect an end to the development of the country between the rivers; until then we can expect a steady increase of produce and population. Realize this, and you then know what it means to speak of the future of the ‘Duab’.

Rickmer-Rickers, Impressions of the Duab (1907)

The short passages in which Rickmer-Rickmers refers to cotton growing in Russian Turkestan show how closely speaking about space is linked to the practices carried out in it. Rickmer-Rickmers already speaks of an almost hysterical attitude of the English press, business and military towards the economic and military measures of tsarist Russia in Central Asia.

Both Rickmer-Rickmer’s 1907 lecture text and Ella Maillart’s much more detailed reportages, which are far less determined by a colonial view of Central Asia, are particularly interesting if one wants to analyse space as a product of social-communicative actions.

Ella Maillart’s visits to the cotton plantations and cotton villages of the Uzbek Soviet Republic in 1931

The unique approach of the Swiss traveller Ella Maillart is that she takes an almost ethnographic approach. And she has access to women. This means that many of her observations are often in contrast to everything that men from Europe have written about the social worlds of Central Asian cultures. The German reporter Egon Erwin Kisch had already interviewed women in 1929, but mainly female officials. Maillart, on the other hand, also talks to many women from the regular working-class and writes about them in her book.

Artificial staging of cotton in propagandistic anniversary publications of the Soviet era.

She visits the Durmen-Baumann-Kolchose, a cotton village about 15 kilometres from Tashkent. In 1930, this kolkhoz, covering an area of almost 200 hectares, had delivered 219 tonnes of cotton, which meant an allocation of twenty-five tonnes of bread.

Some of the irrigation canals she sees there are said to date back to pre-Christian times – Ella Maillart emphasises that only with the introduction of the Soviet system has there been greater justice, with the same working hours for everyone and equal pay. After all, tsarist Russia had also allowed local feudal lords who subordinated themselves to the Russian system to continue to exploit the inhabitants of the villages arbitrarily. However, Ella Maillart also gives negative opinions about the intensified transformation of the agricultural area under the Soviet system:

Do you know what they were doing here? They have given orders to plant cotton everywhere. Then the plough went over the rice fields. It destroyed all our little irrigation canals that had been built and maintained with so much effort for so long. Then, when it turned out that the grain from Siberia was not so easy to get, they said, ‚Grow a third of rice again. But that is no longer possible; all the old water channels are dead.

Ella Maillart, Turkestan Solo (1934)

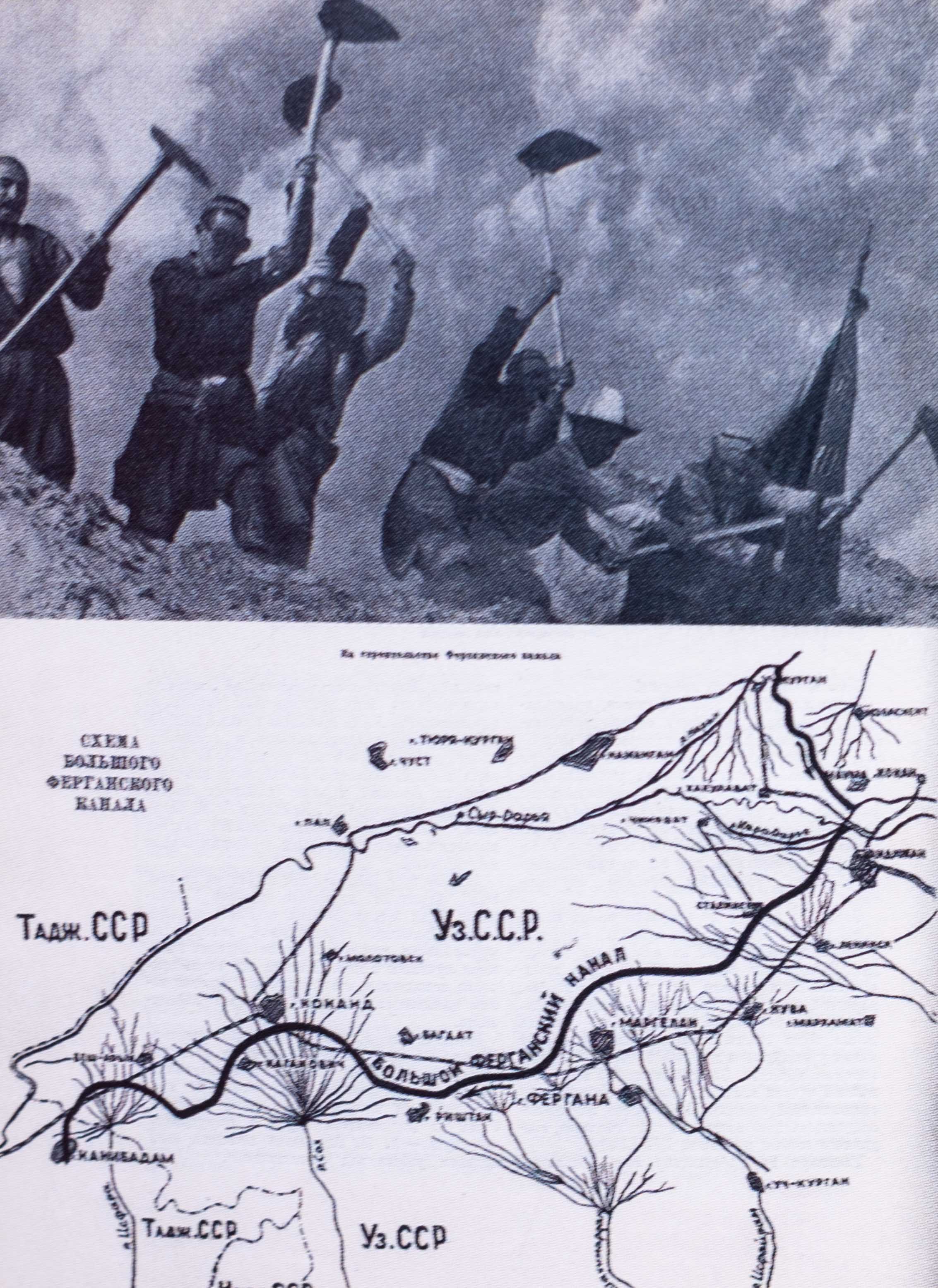

Maillart reports that in 1913 the Ministry of Agriculture of Tsarist Russia had already estimated the length of the canals at over 40,000 km. In a report, the responsible official had expressed admiration for this enormous cultural achievement of the people of the region. During the period of the first five-year plan, the canals were extended many times over. The sowing of cotton began in mid-April, the harvest in July, and lasted until November when frost forced the last capsules to open.

The transformation of the diverse socio-economic cultural space of Central Asia into an area of cotton monoculture required massive human labour and led to a fundamental transformation of established traditional cultural practices.

The women Ella Maillart talks to work on a piecework basis and pick an average of 24 kg a day. They contribute the largest part of the family income. In the beginning, her husbands had opposed the woman taking off her veil and working for the collective farm in the fields. After all, the money the women earned had probably changed almost everyone’s mind. The state takes care of the children while the women work.

There are the pickers; all of them, young and old, look over to me laughing as they see me photographing them. Their faded skirts are turned up and bursting with the snow-white cotton […]. They pick while walking with short, secure handles. […] At one corner of the field, each has her sack, which she fills little by little. I walk through a row of undeveloped parcels to the place where the babies, […] are looked after during working hours.

Ella Maillart, Turkestan Solo (1934)

Propagandistic presentation of child care in the Soviet Uzbekistan of the 1930s

The living conditions in the villages described by Ella Maillart are more than poor during this time. Nevertheless, she likes the small houses. In winter, the rooms, which are built entirely of clay, are kept warm by pouring glowing coal into a rectangle embedded in the ground. Then a table is placed over it and covered with a blanket. In this way, the warmth is maintained while the family sits around the table.

South of the Aral Sea, in Khwarazm, cotton cultivation is also increasing steadily, although the area does not seem to have been safely under Soviet rule at the time that Ella Maillart visits it. Again and again, she reports of attacks by the so-called Basmatchi. This ambiguous description of the group goes back to the Basmatchi, who had initially fought as allies of the Bolsheviks for their cultural self-determination and national independence during the October Revolution of 1917. However, due to the incompatible political goals, an irreconcilable enmity quickly developed between the social-revolutionary Bolsheviks and the Basmatchi. During the civil war from 1919 to 1924, those loyal to the Bolsheviks then called their opponents Basmatchi. In their ranks fought rebels from all kinds of social contexts. They were farmers, descendants of members of the pre-colonial state apparatus or nomads. Until 1920, large parts of Central Asia escaped Soviet rule, although strong Red Army units were operating there. The centres of resistance were the areas around Ferghana, Khiva and Bukhara. Due to the massive Red Army deployment, the Basmatchi armed uprising turned into a gang war by the mid-1920s. The mobile, mostly mounted Basmatchi units were difficult to capture in the steppe and mountains with military and police operations.

Military and economic violence was also used to enforce the cotton economy by linking the right to buy everyday goods and food in the collective shops to participation in the cotton collectives. Ella Maillart’s interlocutor reports:

They have been promised all kinds of benefits. But in practice, they were forced to do so if they wanted to buy anything at all in the cooperatives. These cooperatives have the power of disposal over grain and all other products. The farmers are often told which parts of the land they can plant with barley, maize, rice or fruit trees.

Ella Maillart, Turkestan Solo (1934)

To make socialism attractive, the shops of the cooperatives, for example in Turtkul, the then capital of Karakalpakstan, are better equipped with goods than the centres. What is mainly lacking, however, is grain – this is the negative consequence of the massive introduction of cotton growing, as Ella Maillart describes in many passages of her travel report.

The Aral Sea region in the 1930s

At the beginning of her trip through today’s Uzbekistan, the Swiss traveller visited the editorial office of the newspaper ‚Pravda Vostoka‘ in Tashkent, which was also the headquarters of the propagandistic support of the Soviet cotton offensive. Here, on the one hand, she realised how much the fate of all of Turkestan depends on the fulfilment of the five-year plan: Because the supply of grain and thus the supply of bread is tied to the fulfilment of the plan – a threat from Moscow that nobody in the country doubts will be fulfilled. On the other hand, by fulfilling the plan, Moscow is also addressing the entire Western world and its economic system:

I have today‘, said the editor-in-chief, ‚published the translation of an article in the ‚Frankfurter Zeitung‘ which says that the eyes of the whole world are turned to our Central Asia. We are ruining American and Egyptian trade by producing our own cotton. The example of our republics, freed from the imperialist yoke, will incite the Asian colonies now dominated by France and England to revolt…‘

Ella Maillart, Turkestan Solo (1934)

To be continued…

Text: Stefan Applis (2020)

Photos: Taken from the propagandistic anniversary volumes on the development of the Central Asian Soviet Republics

Reference:

Ella Maillart (1934). Turkestan Solo: A Journey Through Central Asia.

Photography of Ella Maillart via http://www.ellamaillart.ch/index_en.php

1 Thoughts